It is widely known that those who leave their country because of actual (or fear of) persecution do not necessarily carry with them documents proving their identity or the circumstances that led to their flight. And it is also known that survival is often only possible thanks to forged identity or travel documents. According to the Qualification Directive (art. 4 § 5), “where aspects of the applicant’s statements are not supported by documentary or other evidence, those aspects shall not need confirmation” provided that – among other things – “the applicant has made a genuine effort to substantiate his application”; “a satisfactory explanation regarding any lack of other relevant elements has been given”; “the applicant’s statements are found to be coherent and plausible”; and finally “the general credibility of the applicant has been established”.

In line with the UNHCR Manual (1992), the Qualification Directive thus suggests to evaluate the general coherence, plausibility and credibility of asylum seekers’ stories as an alternative to the submission of documental evidence, when the latter is not readily available.

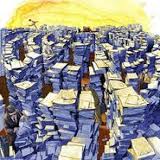

In Italy (like in other European countries), the assessment of the coherence of applicants’ narratives has increased in importance as a means to determine international protection. In many cases, credibility assessment has become the only means, thus replacing the examination of documental evidence; as a consequence, applications are increasingly rejected solely on the ground of a “lack of credibility”.

Yet, the Qualification Directive does not explain how to ascertain narratives’ plausibility or claimants’ credibility. Given the strong link between credibility and narrative, it is crucial to take into consideration how and when such stories are told, in what circumstances, how many times and to whom, knowing that each one of these variables introduces possible changes and variations into the story itself.

Given the strong link between credibility and narrative, it is crucial to take into consideration how and when such stories are told, in what circumstances, how many times and to whom, knowing that each one of these variables introduces possible changes and variations into the story itself.

At a Police Station for the application, in front of first-instance Territorial Commission for the first extended interview, or at appeal before the Tribunal, asylum seekers meet with bureaucrats, translators, lawyers, judges and case-workers; and each time, (parts of) their stories are exchanged, translated, assembled and written down repeatedly in different versions within different types of documents by different subjects.

The stories asylum seekers tell in order to claim international protection are therefore of a peculiar type: they are produced within highly controlled contexts where power relations are heavily asymmetrical; where the pace and rhythm of story-telling are dictated (and interrupted) by the bureaucratic procedure, and the expressive modalities are severely constrained by standard administrative formats; and where those who tell and those who judge do not share the same cultural background, thus producing mistranslations and misunderstandings which are eventually used to cast doubts on the claimant’s credibility.

Despite all this, those who assess asylum narratives’ credibility usually assume (or pretend) that asylum seekers’ accounts flow freely, voluntarily and un-interrupted; that traumatic memory be preserved unchanged across time remaining “consistent” throughout different accounts; that it should come easy to tell intimate (sometime unspeakable) persecution experiences to complete strangers often of opposite sex, or to blindly trust their translating skills.

Social scientists working on issues such as memory and life stories have long discussed gaps, discrepancies and disjunctions between versions of the same story, which change when given at different times or in front of different audiences, and depending on the social context. If this is true for any type of narrative, research on traumatic memory shows that most painful events tend to be recalled in a fragmented and “interrupted” way: far from proving the claimants’ lack of credibility, un-coherent or discrepant versions of the same story may rather testify painful experiences.  The fragmented nature of such stories – linked to past events, but also to the claimants’ changing conditions as time goes by while waiting for their status determination – is further increased by the interview’s modalities. Both first instance commission and appeal judges move forward and backward in the chronology of the applicant’s life history, and systematically interrupt the narrative flow with check-questions (e.g. the name of the Prime Minister of the country of origin, the biggest town, the main bank or river…) in order to assess the claimant’s general credibility.

The fragmented nature of such stories – linked to past events, but also to the claimants’ changing conditions as time goes by while waiting for their status determination – is further increased by the interview’s modalities. Both first instance commission and appeal judges move forward and backward in the chronology of the applicant’s life history, and systematically interrupt the narrative flow with check-questions (e.g. the name of the Prime Minister of the country of origin, the biggest town, the main bank or river…) in order to assess the claimant’s general credibility.

Yet, this type of questions generate further confusion in asylum seekers, who expect to be interviewed about their story of persecution but find themselves interrogated and tested, their stories scrutinized in detail in order to seek out inconsistencies and lies.

To assess credibility, the Qualification Directive also refers to elements of the story which “do not run counter to available specific and general information relevant to the applicant’s case”. In this respect, it is the duty of the Member State to assess elements of the application taking into account “all relevant facts as they relate to the country of origin at the time of taking a decision on the application; including laws and regulations of the country of origin and the manner in which they are applied” (art. 4 § 3).

Yet, in Italy additional information on the country of origin is often not specifically acquired by decision makers, who mostly seem to ground their assessments on personal believes and shared common knowledge. In this case, the different cultural and political background can result in negative credibility finding.

This is what happens with witchcraft: a complex system of beliefs embedded in (and regulating) social relations in many countries, some of which list it in their Penal code alongside other crimes. A consistent anthropological literature describe witchcraft’s functions and meaning in various contexts; as a form of collective violence on individuals regulating social tensions, it can be resolved in customary courts and can result in the death of the accused.

Despite scholarly research documenting witchcraft functioning, protection claims advanced by those accused of witchcraft are always rejected, since decision makers find little coherence in complex cultural and social aspects which appear too distant from their own.

But stories recalling types of persecution more generally known and widely documented in international reports can likewise result in rejection for negative credibility. Some decision makers found little credibility in the story of those who, having been tortured with other persons, testified to be the only one released, despite the sadly common practice to leave one witness as a public warning.

Others believed documents certifying medical care provided by the perpetrators of the violence were a forgery, despite this practice being widely documented as a deterrent and public display of impunity.

Finally, it is considered generally un-plausible that someone may escape prison thanks to the compassionate intervention of a prison guard. Here, what seems in-credible to decision makers is that someone may put his own life at risk in order to save the life of an innocent prisoner, often a stranger.

When confronted with this type of rejection, it is difficult not to think at the many stories of European Jewish citizens who survived during world war II thanks to other citizens who hid them or helped them escape, often at their own risk: today, those survivors would not be taken as credible.

* Barbara Sorgoni is lecturer in Cultural Anthropology at the University of Bologna. She has done extensive research on the anthropology of Italian colonialism (Parole e corpi. Antropologia, discorso giuridico e politiche sessuali interrazziali nella colonia Eritrea, Liguori, Napoli 1998; Etnografia e colonialismo. L’Eritrea e l’Etiopia di Alberto Pollera, Bollati Boringhieri, Torino 2001) . She is currently doing research on the institutionalization of asylum procedures in Italy and the role of narratives and documents, on which she edited Etnografia dell’accoglienza. Rifugiati e richiedenti asilo a Ravenna, CISU, Rome 2011; “Chiedere asilo in Europa. Confini margini e soggettività”, Lares, vol. LXXVII, n.1, 2011.